Table of Contents

ModRuby is designed to be extremely flexible. Its main function besides embedding Ruby within Apache is to provide a configurable interface with which to invoke Ruby code from Apache in a variety of ways — from executing the most bare-bones CGI scripts to hooking in entire web frameworks.

Connecting ModRuby to your code is all done via Apache configuration directives. There are endless ways you can do this, but it’s all ultimately pretty simple. We will cover the necessary Apache configuration mechanics and work through many different scenarios which should give you a good feel for how everything works and what you can do.

Everything is done in the context of handlers. Apache has many different

kinds of handlers for different stages of the request handling process, but the

most basic and common by far is the “content generator.” That’s where you, well,

generate content ... which is basically what everyone thinks of server-side web

programming anyway. That said, all handlers in ModRuby are in Apache parlance

“content generators.” We will call these “module handlers.” These handlers are

written in C and reside in the ModRuby module and they can be invoked from the

Apache configuration as canonical Apache handlers. When you load the

mod_ruby.so module in Apache, these handlers become

available for you to use.

To be useful, a module handler must be linked up to a Ruby method of some kind. We refer to these Ruby methods as just “Ruby handlers” — they are what handles the request. There are three parameters that must be specified to link a module handler to a Ruby method:

Module: defines the Ruby module specified via the RubyrequiredirectiveClass: specifies the class name within the respective module. This can be qualified with one or more module namespace prefixes (e.g.Juji::Fruit)Method: specifies the method name within the class. This method takes exactly one argument which is used to pass in the Apache request object for the specific request being handled.

With these, the ModRuby module can load the Ruby module, instantiate an object

of the given class, and then call the specified method, passing in the current

request, which is an instance of the Apache::Request

class. From that point on, it is up to the Ruby method to service the request

(e.g. generate content). That’s the whole process. So configuration is thus the

process of connecting module handlers (C functions in the

mod_ruby Apache module) to Ruby methods in your files, and

this is all done by specifying these connections in the Apache configuration

file(s).

As with any Apache configuration, you can define all the file types, locations, directories and various other conditions under which your Ruby handler(s) should be called. There are almost limitless possibilities for how you can route requests to handlers. The whole point of all the different module handlers to simply to route the request to the right Ruby handler, and from that point on, it’s all Ruby. Module handlers are just Apache-configurable connectors that give you fine grained control over (1) what handlers are invoked, (2) under what circumstances, (3) in what specific configuration contexts.

In the Apache configuration file, there are two independent phases you must address in order to connect a web request to your Ruby handler:

You specify the specific condition(s) in which the module handler is to be invoked. This connects the Apache request with a specific ModRuby handler.

You associate the ModRuby handler with a specific Ruby method that is to service the request. This completes the route from Apache request to Ruby code.

That said, there are two classes of module handlers: script handlers and framework handlers. Script handlers exist specifically for processing RHTML and optimized Ruby (CGI) scripts. Framework handlers, on the other hand, are completely open-ended: they allow for a high degree of specificity under which conditions they are run and allow you to add custom configuration variables for each handler that are passed into the handler’s Ruby environment. They are designed to connect to bigger, more complex environments (e.g. frameworks).

The script handlers are targeted at processing RHTML and Ruby CGI

scripts. They consist of the ruby-rhtml-handler and

ruby-script-handler configuration values, respectively. To

use them, you would do something like the following in your Apache

configuration:

<IfModule ruby_module>

AddHandler ruby-rhtml-handler .rhtml

AddHandler ruby-script-handler .rb .ruby

# Or perhaps

<Files ~ "\.(rhtml)$">

SetHandler ruby-rhtml-handler

</Files>

# And maybe

<Location /ruby-cgi>

SetHandler ruby-script-handler

</Files>

</IfModule>

You have to understand a little about Apache configuration file syntax for this

to be crystal clear. Let’s take just the first two lines (the remaining examples

of Apache directives will be covered later). The first two lines use Apache's

AddHandler directive to tell Apache that if it sees a file

with the extension of .rhtml to call the

ruby-rhtml-handler handler. Similarly, if it sees a file

with an extension of .rb or .ruby, to call

the ruby-script-handler. Both of these handlers are just C

functions in the mod_ruby.so module. Basically, these

directives will cause Apache to pass control to these C functions for requests

that ask for files with .rhtml, .rb or

.ruby extensions. This takes care of phase 1.

Now we have to connect these module handlers to Ruby handlers (phase

2). With script handlers, we do this using two ModRuby directives:

RubyDefaultHandlerModule and

RubyDefaultHandlerClass. They specify the Ruby module and the

class within that module that contains the handlers. ModRuby includes a default

module that implements both handlers, called

modruby/handler. Its implementation is as follows:

module ModRuby # This implements the generic request handlers, specifically the (Ruby) script # and RHTML handlers. class Handler # RHTML script handler def rhtml(req) Runner.new(req).runRhtml() end # Ruby script handler def script(req) Runner.new(req).runScript() end end end # module ModRuby

There is one method for the RHTML handler and one method for the script

handler. The Runner class is just a cleanroom environment

with which to run code in. The environment (global namespace) in which the code

runs will be completely erased when the Runner object

destructs, and all objects and memory allocated by the handler freed. Thus each

script runs in a clean, self-contained environment which is completely disposed

of when the Ruby handler finishes.

So, returning to the configuration example (using only the first two lines we covered) we make the full connection — phase 1 and phase 2 — with the following:

<IfModule ruby_module> # Phase 1 -- Apache to ModRuby AddHandler ruby-rhtml-handler .rhtml AddHandler ruby-script-handler .rb .ruby # Phase 2 -- ModRuby to Ruby RubyDefaultHandlerModule 'modruby' RubyDefaultHandlerClass 'ModRuby::Handler' </IfModule>

Notice in phase 2 that we have only specified the module and class. But

what about the methods? Well, the script handlers are hard-coded to use fixed

method names. That is, the ruby-rhtml-handler is hard coded

to always call a method named rhtml() and likewise the

ruby-script-handler always calls a method named

script(). They are fixed. So you can specify any module

(RubyDefaultHandlerModule) and class

(RubyDefaultHandlerClass) you want, but within that class,

the script handlers will look for methods within the class that are named

rhtml() or script() (depending

on the handler).

Furthermore, since they both use the same module and class specification,

if you want to override the default RHTML or script handlers, your override

class has to provide both methods. However, there is

nothing to stop you from delegating the method you don’t want to implement to

ModRuby::Handler. For example, say you wanted to write

your own script() handler, but wanted to use the

default ModRuby RHTML handler. You could create your module/handler as follows:

require 'modruby/handler' module MyModule class Handler # Ruby script handler def script(req) # Your script handler implementation here end # Use the default ModRuby RHTML script handler def rhtml(req) handler = ModRuby::Handler.new() return handler.rhtml(req) end end end # module

Assuming you place it in a file called mymodule.rb

with the Ruby path, you would then update your Apache configuration to point to

it as follows:

<IfModule ruby_module> # Phase 1 -- Apache to ModRuby AddHandler ruby-rhtml-handler .rhtml AddHandler ruby-script-handler .rb .ruby # Phase 2 -- ModRuby to Ruby RubyDefaultHandlerModule 'mymodule' RubyDefaultHandlerClass 'MyModule::Handler' </IfModule>

Now all RHTML and CGI script handlers will be handled by your module.

ModRuby uses an RHTML framework that works exactly like eRuby to parse RHTML

files. ModRuby originally used eRuby for RHTML processing, but there were

problems getting it to work with Ruby 1.9.1 when it came out. This led to the

development of an eRuby clone — the ModRuby RHTML parser — a flex-based scanner which is compiled

directly into mod_ruby as a native Ruby C extension. It

exactly follows the rules of eRuby. Thus all of the rules in eRuby apply to

creating RHTML documents in ModRuby. Just to be complete, let's cover the gamut

of RHTML (which may take at most a paragraph).

Note

ModRuby includes an alternate RHTML delimiter syntax. In addition to angle brackets, braces can be used instead. This form supports embeddeding RHTML within XHTML, XML, etc. where the angle brackets can cause problems.

Let’s begin with the obligatory example:

helloworld.rhtml, which is as follows:

Hello World. This is <%=ModRuby.name%>

If you don’t already have the page loaded, you this link and look at the result. Simple enough.

RHTML allows you to embed Ruby code in text and run it in the order that it appears. There are three basic constructs for embedding code. First there is embedding an entire chunk of code, as follows:

Here is some text <% puts "Inside these delimiters, here is Ruby code" %> Outside it's just plain text again.

Then there is inline printing:

Printing text <%="in line"%>

Whenever RHTML sees the <%= opening tag, it prints

everything that follows. You can think of the equals sign as shorthand for a

puts command.

Then there is a third construct which is really a function of the first. You can

express blocks over several segements of code and text as follows:

<%array.each do |something|%> This entire text block will be printed with the current value of <%="something%> for each iteration of the loop. <%end%>

And that's about it — RHTML in a nutshell.

Framework handlers are more flexible than script handlers and have extended features. There is no default implementation for framework handlers. Basically, ModRuby passes your Ruby method an Apache request object and you’re on your own.

Framework handlers are implemented using the

ruby-handler C function in the ModRuby module. One way to

declare a framework handler is by using the AddHandler

directive like above. Say for instance we wanted to create a handler for

“sheepdip” files (which we designate as having a .dip

extension). We could start by doing the following:

<IfModule ruby_module> AddHandler ruby-handler .dip </IfModule>

There’s phase 1. Going this route, we now use the

DefaultHandler variables for phase 2 — connecting the

framework handler to a Ruby method. We specify the module/class/handler using

the RubyDefaultHandlerModule,

RubyDefaultHandlerClass and the (new)

RubyDefaultHandlerMethod directive, respectively. Notice

already one difference between framework handlers and script handlers: you can

specify the Ruby method name via the RubyDefaultHandlerMethod

directive. Whereas the method name is fixed in script handlers, it’s

parameterized in framework handlers.

Say our fictional sheepdip files use our fictional

sheepdip/handler module, which contains our

Sheepdip::Handler class which contains a

handle() method. One way to use it would be to set our

configuration as follows:

<IfModule ruby_module> # Phase 1 -- Apache to ModRuby AddHandler ruby-handler .dip # Phase 2 -- ModRuby to Ruby RubyDefaultHandlerModule sheepdip/handler RubyDefaultHandlerClass Sheepdip::Handler RubyDefaultHandlerMethod handle </IfModule>

To summarize, the three default handler directives are as follows:

RubyDefaultHandlerModule: specifies the Ruby handler module to use via the RubyrequiredirectiveRubyDefaultHandlerClass: specifies the Ruby handler class name within the respective moduleRubyDefaultHandlerMethod: specifies the Ruby handler method name within the respective class

But you say “yeah, but isn’t setting the

RubyDefaultHandlerModule and

RubyDefaultHandlerClass parameters going to redefine how

script handlers run as well?” Yes, it will. Unless you also include

rhtml() and script() methods

in your new default module/class, which is kind of silly and painful, it will

break the default behavior used for servicing script handlers. That’s why there

is another (better) way to go about connecting framework handlers.

You can skirt the DefaultHandler directives entirely

and set up your own independent handler with the more general

RubyHandler directives. These directives are as follows:

RubyHandlerDeclare: Declares a new framework handler.RubyHandlerModule: Defines the module for a given framework handler.RubyHandlerClass: Defines the class for a given framework handler.RubyHandlerMethod: Defines the handler method for a given framework handler.

These work similarly to the default handler directives, but they take as an argument the name of the framework handler to define. They are not defaults; they are specifics. To use this approach, we would change our configuration to something like the following:

<IfModule ruby_module>

# Phase 0 -- Define framework handler

RubyHandlerDeclare SHEEPDIP

RubyHandlerModule SHEEPDIP sheepdip/handler

RubyHandlerClass SHEEPDIP Sheepdip::Handler

RubyHandlerMethod SHEEPDIP handle

# Phase 1 -- Apache to ModRuby

<Files ~ "\.(dip)$">

SetHandler ruby-handler

# Phase 2 -- ModRuby to Ruby

RubyHandler SHEEPDIP

</Files>

</IfModule>

In "Phase 0", the SHEEPDIP argument is just a unique key used

to declare and reference a given framework handler. When you declare a framework

hander, the ModRuby module creates an entry in an internal hash table of

framework handlers, using the name as the key. Thus you can define as many

framework handlers as you like, the only constraint being that they must all

have unique names. The framework hander’s entry (value) in the hash table is

itself a hash table, and can thus store an unlimited number of key/value pairs

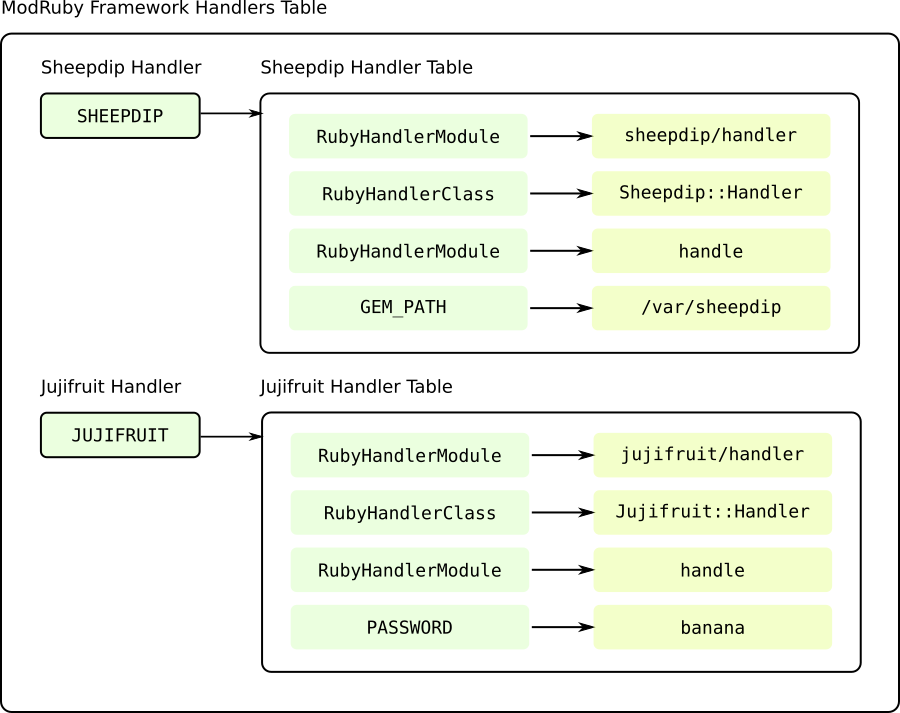

just for that handler. So what you have is a hashtable of hashtables as follows:

The outermost hashtable is the internal ModRuby framework handlers table, which

is filled with each framework handler you define. In this example there are two:

SHEEPDIP and JUJIFRUIT. Each defined

framework handler in turn has its own name (e.g. SHEEPDIP)

and hashtable in which its respective Ruby module, class and handler method

variables are stored. But the framework handler’s hashtable can also hold an

unlimited number of other key/value pairs as well, which you can use to

customize and/or configure your framework handler. In this example, there is a

custom GEM_PATH variable set in the

SHEEPDIP handler’s table, and a PASSWORD

variable JUJIFRUIT’s. These are added using the

RubyHandlerConfig directive, which is covered later. For now,

all you need to know is that the RubyHandler directives are

stored there and provide all the information needed to invoke the

handler.

So with the first four lines (phase 0) we have defined our

SHEEPDIP framework handler. Next we need to tell Apache to

associate .dip files to the

ruby-handler (phase 1), and from there connect it

(ruby-handler) to our SHEEPDIP handler

(phase 2). To do this, we are going to do things a little different here. We are

not using the AddHandler directive. We could, but here we are

going to use a different approach just to illustrate we have with Apache’s

various configuration directives. As we are interested in only files with

extension .dip, we use a Files directive

to match this extension. Within the block we use SetHandler,

which unconditionally sets the Apache handler to

ruby-handler, rather than AddHandler

outside. This just keeps us from having to repeat ourselves, as

AddHandler requires us to again specify the extension, which

we’ve already done in the Files directive. This approach is

just a little cleaner. Either way, we are just associating the specific file

extension .dip to ruby-handler —

that’s the point here, and you can do that however you like.[1]

Next is phase 2, where we weld the ruby-handler to the

SHEEPDIP framework handler using the

RubyHandler directive. The RubyHandler

directive is a block-level directive which unconditionally sets the specified

framework handler to use in that scope.

So based on the contents of the Files block, when

Apache sees a file with extension .dip, it will invoke

ruby-handler. When ruby-handler

executes, it in turn will see the RubyHandler directive set

internally to use the SHEEPDIP Ruby handler. Knowing this,

when ruby-handler processes the request, it will pull the

SHEEPDIP handler entry from the internal handlers table,

extract the RubyHandlerModule,

RubyHandlerClass and RubyHandlerMethod

entries stored there and use them to invoke the Ruby module/class/method,

effectively routing the request to our Sheepdip handler. From there, it’s all up

to our Ruby code in the Sheepdip::Handler::handle()

method. The Ruby handler will have access to the SHEEPDIP

handler table, which includes the custom configuration variables (i.e. the

GEM_PATH variable in this example). We will cover how that

works in the next section.

An access handler implements the Apache

ap_hook_check_access_ex() handler. This is a special

handler that inspects the request headers or request body and makes an

authentication and authorization decision. This handler is run before other

handlers and is a nice method to separate authentication code from

content.

If the user passes the checks, nothing happens and the RubyHandler or any

other handler is run. This is also compatible with any other content handlers

like mod_cgi, mod_dir,

mod_autoindex, etc.

If the user fails your authentication/authorization check, the error response can be an HTTP 401 Unauthorized response to request Basic auth or OAuth2 bearer tokens. Or something more simple like a redirect to an authentication system.

Here is an Apache config example for setting up a Framework Handler that is used as an Access Handler:

RubyHandlerDeclare ACCESS_TEST RubyHandlerModule ACCESS_TEST "/var/www/html/access_test.rb" RubyHandlerClass ACCESS_TEST AccessTest::Handler RubyHandlerMethod ACCESS_TEST check_access <Directory "/var/www/cgi-bin"> RubyAccessHandler ACCESS_TEST </Directory> <Directory "/var/www/html"> RubyAccessHandler ACCESS_TEST </Directory> RubyHandlerDeclare DECLINED RubyHandlerModule DECLINED "/var/www/html/declined.rb" RubyHandlerClass DECLINED Declined::Handler RubyHandlerMethod DECLINED check_access <Location "/assets"> RubyAccessHandler DECLINED </Location

Some pseudocode that might be used as access_test.rb:

module AccessTest

class Handler

def check_access(request)

if authorized?

request.set_user(@username)

else

r.setStatus(401)

r.headers_out['WWW-Authenticate'] = "Basic"

end

end

end

end

In some cases, you might want to exclude some paths from authentication,

like assets. Since you can’t remove a RubyAccessHandler, we

can set a new one that does nothing but return. It’s lightweight, and doesn’t

add the extra overhead of authentication.

module Declined

class Handler

def check_access(request)

end

end

end

There are two classes of module handlers: script handlers and framework

handlers. There are two subclasses of script handlers: RHTML and CGI. Script

handlers are created for convienience. Their purpose, along with the

DefaultHandler directives are just to make it as easy as

possible to get something going. They exist just for the sake of

simplicity. They require very little knowledge or work to get Ruby code running

within Apache.

Framework handlers offer greater control, specificity, and features than

script handlers, but require a little more effort and understanding. They

slipstream into Apache’s native configuration directives such as

Directory, Location, and

File, giving you tremendous flexibility and fine-grained

control over what handlers fire and under what conditions, with the option of

adding custom configuration settings with each handler. We will soon see that

they even enable you to build upon, override and merge directives for different

directories, locations and files.

To set up a for framework handler, you have to follow three basic steps:

Declare and define one or more framework handlers using

RubyHandlerDeclare,RubyHandlerModule,RubyHandlerClassandRubyHandlerMethoddirectives.Tell Apache to call the

ruby-handlerhandler using<Files>,<Location><Directory>contexts with either theAddHandlerorSetHandlerdirectives. This is phase 1.Connect the

ruby-handlerto the specific framework handler using theRubyHandlerdirective. This is phase 2.

As a result, you can create an unlimited number of different handlers for different files, directories, locations, extensions and contexts.